In writing this series I have up to now, had some connection or personal interest in the subject prior to deciding to write the article but with this one it was finding a picture that intrigued me. Though I have worked in and around Earls Court at various odd times in my career, my earliest visits were at the beginning in 1975 when I had to get off at Earls Court tube station and exit the Warwick Road end in order to walk up to Charles House, where the Post Office then had a training school.

In writing this series I have up to now, had some connection or personal interest in the subject prior to deciding to write the article but with this one it was finding a picture that intrigued me. Though I have worked in and around Earls Court at various odd times in my career, my earliest visits were at the beginning in 1975 when I had to get off at Earls Court tube station and exit the Warwick Road end in order to walk up to Charles House, where the Post Office then had a training school.As you leave the station the Earls Court exhibition centre opposite is quite a sight. As a working class south London lad this was my first sight of the famous exhibition centre. The land it occupies was once an awkward triangle of railway tracks, sidings and depots owned by the Earl of Zetland from who it gets its name. Opened in September 1937, the exhibition centre cost £1.5m and was designed by Chicago architect, C Howard. At the time it was the largest reinforced concrete structure in existence.

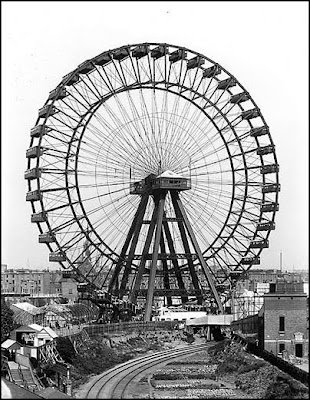

Exhibitions on the site predate the building however and if I had been there at the turn of the last century I probably would have been even more impressed with the view of the area, as I would have seen the “Gigantic wheel”. Originally built as part of the Empire of India Exhibition in 1895, it stayed there 11 years.

Looking reminiscent of the “London Eye” on the South Bank, the “Gigantic wheel” was also an observation wheel, one of a series of such wheels, the first of which was the “Ferris wheel” at the Chicago Exhibition of 1893. It was this wheel which gives all such “big wheels” their America name and provides another, earlier, connection for the Earls Court site to Chicago. The name came from its designer, George Washington Gale Ferris, whose idea was for an “observation wheel 250 feet high”.

Construction work began on the larger Earls Court wheel in March 1894 when massive concrete footings were put in and it was opened to passengers in July 1895. It had a diameter of 300ft, (larger than the original American one), weighed 1,100 tons and completed one revolution in about 25 minutes. Originally there were to be ‘recreation towers’ on either side with lifts carrying visitors up to the axle, through which it would have been possible to walk, but this was not carried through. The wheel was rotated by means of two 50HP steam engines. Each of the forty cars could accommodate forty passengers so that up to 1,600 could ride the on the wheel together, when it was said that from the top you could see Windsor Castle.

In 1896 another wheel was opened in Blackpool. That big wheel was 214 feet high, and rotated every 15 minutes compared with the 25 minutes of its London rival. It was not tremendously successful however, perhaps because the tower at 519 feet, over twice the wheel’s height, overshadowed it, and it closed relatively quickly.

The final one was built in Vienna; that wheel lasted ‘til it was bombed during the war but it was rebuilt after the war and still exists today. You may remember it in films like “The Third Man” and “The Living Daylights”

Our Earls Court “Gigantic Wheel” suffered an embarrassment in May 1896 when it got stuck for four and half hours. The passengers were handsomely compensated for their ordeal though and this increased its popularity for a while as people hoped they could get a ride and make a profit into the bargain. It was reported that the following day there was a queue of approximately  11,000 people all hoping to get stuck in the wheel and claim their five pounds compensation! Despite this the Earls Court “Gigantic wheel” survived until 1906 when it was demolished because it was no longer profitable. In its life it had conveyed two and a half million passengers.

11,000 people all hoping to get stuck in the wheel and claim their five pounds compensation! Despite this the Earls Court “Gigantic wheel” survived until 1906 when it was demolished because it was no longer profitable. In its life it had conveyed two and a half million passengers.

It was said that it was “a pity that all the ability and cost expended in its construction should not have been devoted to some more useful end than carrying coach loads of fools round a vertical circle’’.

However in spite of such views, (and if you pardon the pun), if it had been in a more central location then, judging by the London Eye, perhaps it would still have been here today. I’ll never look at the London Eye or Earls court in quite the same way again.

Laurie Smith